April 13, 2006

© Janet Davis

Ranunculus is such a strange, bumpy word. It certainly doesn’t suit the

delightful, crepe paper petals and symmetrical, rose-like blossoms of Persian

buttercups (Ranunculus asiaticus) found at greengrocers and garden

centres now.

Ranunculus is such a strange, bumpy word. It certainly doesn’t suit the

delightful, crepe paper petals and symmetrical, rose-like blossoms of Persian

buttercups (Ranunculus asiaticus) found at greengrocers and garden

centres now.

The word ranunculus comes from the Latin for “little frog” and more accurately describes the moisture-loving, yellow buttercups ( e.g. R. acris) to which Persian buttercups are related. The common name comes from the fact that the wild plant grows on rocky limestone hillsides in North Africa, Crete and parts of the Middle East including Iran, once called Persia. Although the species has single red or yellow flowers, today’s hybrid strains feature gorgeous, double blossoms in a rainbow of delicious colours and bi-colours.

The cultivation of Ranunculus asiaticus goes back more than 350 years. According to an article by Timothy Clark in the Royal Horticultural Society journal The Garden, the first plants were brought to Europe from the Levant (the old name for regions bordering the eastern Mediterranean) in the 17th century by bulb traders who were also importing the first tulips and anemones. Cultivated seedlings of Persian buttercup proved highly variable in colour and were often infected by viruses which caused the colour to “break” (like the Rembrandt tulips of Tulipmania fame), causing bizarre patterns, stripes, spots and contrasting edges. Breeders went to great lengths to keep the best “breaks” ongoing by dividing the tubers, rather than growing uninfected plants from seed. The plants were so popular with “gentlemen florists” that before World War I, it was estimated that for every tulip cultivar, there were ten ranunculus cultivars. Today, the old varieties have disappeared; newer ones are much more resistant to viruses.

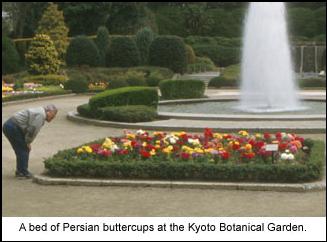

The most spectacular display of Persian buttercups I’ve seen was in the Kyoto Botanic Garden where a mass April planting in jewel-like colours completely overshadowed the tulips and Japanese cherry trees nearby. Isolating them in their own small planting really makes sense because like all floral prima donnas, they don’t integrate particularly well in a spring border with shrubs and early perennials.

In warm (Zone 8-10) coastal areas like Southern California, the tubers are planted outdoors in fall for early spring bloom. But since plants suffer damage at 2C, in colder regions the tubers are sold in spring, just like begonias and dahlias. They’re best started in pots indoors under lights, then planted out in the garden after the risk of frost has ended. Unlike other summer bulbs, Persian buttercups prefer cool nights (5-10C) and sunny, mild days (less than 18C) and will quickly go dormant in our warm summer weather. For this reason, they’re also offered in spring as forced greenhouse plants ready to tuck into the garden or a planter.

To try your hand at starting the tubers indoors under grow-lights, soak them in warm water for several hours first. Plant one to a pot, about 5 cm deep in rich, well-drained potting soil that’s moist, but not soggy. Make sure the little claws or prongs are facing downward. Once the celery-like foliage is well-developed and flower buds have formed, feed them every 2 weeks with a soluble fertilizer (15-30-15 is good) diluted to half strength. Don’t over-water the soil and avoid getting water in the crown, which can cause root rot. Once they’re planted outdoors (in a protected location where those sumptuous flowers won’t get whacked by wind and rain), deadhead old blooms regularly to keep new ones coming. Since it’s tricky to store ranunculus tubers through winter and they’re so inexpensive, my suggestion is to buy fresh ones each year.

Persian buttercups make exceptional cut flowers, lasting a long time in arrangements. At this time of year, I love including them in tiny egg cups along with other seasonal blooms. And they’re lovely in outdoor containers with pansies, forget-me-nots, primroses and the smaller spring-flowering bulbs like grape hyacinth and dwarf narcissus.

Adapted from a column that appeared in the National Post