March 2007 © Janet Davis

Maasai Mara: March 4 – 6:

We landed in Arusha where we

cleared Tanzanian customs, then boarded a SafariLink Dash-8 for the short

flight to  reboarded the plane carrying a boxed snack to

tide us over on the last leg of our journey to the Maasai Mara.

reboarded the plane carrying a boxed snack to

tide us over on the last leg of our journey to the Maasai Mara.

At the Ngerende airstrip, we were

met by six safari vehicles belonging to the Mara Safari Club. Our driver Evans greeted us warmly and threw

our duffel backs in the back for the short drive to the camp. Built on an oxbow of the hippo-filled

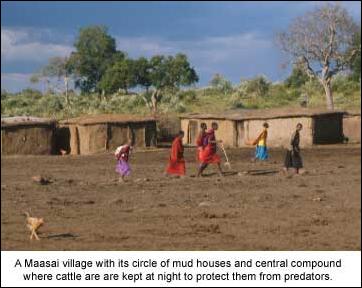

He told us that the Mara, a

Maasai word that means “spotted with trees”, is a conservation area, not a game

reserve, so the Maasai people live here along with the wild animals. There are 12 Maasai clans totalling about

400,000-500,000 individuals, and the clans are related by bloodline. Their villages are named after the clan  name or that of an elder, and clan leaders

have the job for life. Maasai believe in

“a living God and reincarnation”. Each

village has a medicine man, but medicine “brought by the missionaries” is also

used. Pastoralists, they live mostly on

the low plains where they keep and graze their cattle, which are occasionally

sold to get money.

name or that of an elder, and clan leaders

have the job for life. Maasai believe in

“a living God and reincarnation”. Each

village has a medicine man, but medicine “brought by the missionaries” is also

used. Pastoralists, they live mostly on

the low plains where they keep and graze their cattle, which are occasionally

sold to get money.

Polygamy is still practised by many Maasai, with the parents selecting the son’s first wife and presenting a dowry of 5-8 cows to the bride’s father. The role of the women is to have children, build the mud-and-dung homes, train the young girls in décor and beadwork, milk the cows, haul the water, gather firewood and keep the fire going. At 8 to 10 years, the boys become cattle herders. One of the rites of passage for a Maasai boy is circumcision and William explained that it’s a badge of strength not to move a muscle during this procedure. William said that girls are no longer circumcised (though press reports indicate that this practice has not ended in all Maasai settlements.) Young children are now being sent out of the villages to school.

The Maasai diet always fascinates outsiders for it was traditionally meat, cow blood, milk and herbs – a combination some male Maasai credit for their beautiful, smooth complexions. The blood is harvested from a cow’s jugular vein through a surgical incision made with a sharp, semi-circular arrow, a procedure that can be carried out on the same cow up to once a week. The fresh blood is gathered in a calabash husk and mixed with milk and medicinal herbs. Fresh cow dung is used to dress the neck wound. In reading more later, I found that in recent times, cereal crops such as millet and maize have been grown by the Maasai and the corn is mixed into a porridge called uoali.

William showed us the three implements a Maasai man carries with him: a walking stick or “third leg”, so-called because it’s used to lean on as they watch their cattle graze; a club/hammer made from the brown olive wood and used for breaking fruits and crushing bones for their marrow; and a macheté. He explained that red has always been a favorite color for male garments because traditionally, in warfare, it was advantageous not to let the enemy know which of your warriors had been bloodied. (However, we learned from our safari driver that it’s not the red color of the robes that frightens lions, which are color-blind; rather, the lion knows the tall, slender shape and walking gait of a spear-bearing Maasai and avoids him). Willilam finished his talk by inviting us to join him on a visit to a nearby Maasai village or manyatta.

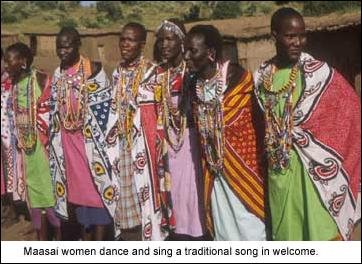

As our vans approached the

village, we were met by a procession of colorfully-dressed women who sang and

danced barefoot,  eventually leading us inside the village to

the central compound with its dirt floor bearing fresh evidence of the cows

that are brought here each night to protect them from the lions and hyenas

outside. Chickens pecked at the dirt and

small children awaiting their turn to sing

waited in the distance. The

afternoon sun beat down as the women beckoned to the visitors to join them in

the dance. Then it was the turn of a

half-dozen morani, young Maasai warriors who had a jumping contest to see who

could leap the highest with the least apparent effort. Finally, the children were called forward and

led in their tuneful ABC’s by a spirited boy of seven or eight.

eventually leading us inside the village to

the central compound with its dirt floor bearing fresh evidence of the cows

that are brought here each night to protect them from the lions and hyenas

outside. Chickens pecked at the dirt and

small children awaiting their turn to sing

waited in the distance. The

afternoon sun beat down as the women beckoned to the visitors to join them in

the dance. Then it was the turn of a

half-dozen morani, young Maasai warriors who had a jumping contest to see who

could leap the highest with the least apparent effort. Finally, the children were called forward and

led in their tuneful ABC’s by a spirited boy of seven or eight.

A fire-starting demonstration was next, with some of the men showing us how they twirl a stick of African red cedar against soft sandpaper wood or olseki (Cordia monica) until sparks appear. Then we were invited to go under the low doors of the bomas and see how the villagers sleep, cook and eat.

Finally, we were escorted to a field just

behind the village where the women had laid out their beadwork, spoons, bowls

and other crafts. Now we were on a

different footing; the respectful distance closed and hard bargaining ensued. “Look,

look! Look here!” they cried. “This

one! This one!.” A few male Maasai floated around the

perimeter, helping the women negotiate.

We made our purchases and waved goodbye.

Finally, we were escorted to a field just

behind the village where the women had laid out their beadwork, spoons, bowls

and other crafts. Now we were on a

different footing; the respectful distance closed and hard bargaining ensued. “Look,

look! Look here!” they cried. “This

one! This one!.” A few male Maasai floated around the

perimeter, helping the women negotiate.

We made our purchases and waved goodbye.

Though we knew the little pageant was a routine production for lodge guests in the area, it was nevertheless interesting to get a glimpse at lives so different from ours and so closely aligned to nature.

Back in the van, Evans wanted to

make the most of what was left of our first afternoon on the Mara. The light was amazing, the grasses golden

and the sky a tumult of clouds with rain falling in the distance. Small groups of topi were grazing beside

the road and a long procession of giraffes made their way across  the Mara, clearly aiming to be somewhere

before dark. I was struck by the regular

linear patterns of the Mara: lines of

treed gullies; then grasses; more treed gullies; more grasses, and on. We would learn from the lodge’s naturalist

the next day that trees grow in long cracks in the subsoil, thus the

uniformity.

the Mara, clearly aiming to be somewhere

before dark. I was struck by the regular

linear patterns of the Mara: lines of

treed gullies; then grasses; more treed gullies; more grasses, and on. We would learn from the lodge’s naturalist

the next day that trees grow in long cracks in the subsoil, thus the

uniformity.

There had been so much rain that

many of the low spots on the Mara’s roads had turned into gumbo. As we headed down into one of the shallow

gullies, the 4-wheel in front of us slowed a second too long and became

instantly mired in the mud. Rocking and

revving had no effect so the driver jacked up the wheels while Alfred, our

Micato guide and William, the Maasai, went looking for large rocks to place

beneath them. Night was falling and a

few of the women began looking nervously at the croton thickets and high

grasses on either side of us. Was it

time for the lions to come out to hunt, they joked? Finally, they were ready. The driver jammed his foot on the gas and the

van lurched upward and forward, its tires finding purchase on the grassy bank

ahead. Our turn now. Two of the occupants of our  van drove 4-wheels on their horse farm back

home. “Don’t stop, Evans,” they

said. As he charged through the muddy

bottom, twisting and turning and spinning his wheels, we screamed

encouragement: “Keep going, keep going,

keep going! Yes, yes, YES!!” We roared up the opposite bank cheering and

clapping. “All right, Evans!!”

van drove 4-wheels on their horse farm back

home. “Don’t stop, Evans,” they

said. As he charged through the muddy

bottom, twisting and turning and spinning his wheels, we screamed

encouragement: “Keep going, keep going,

keep going! Yes, yes, YES!!” We roared up the opposite bank cheering and

clapping. “All right, Evans!!”

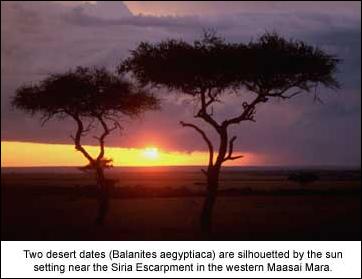

As we drove toward camp, we gazed back at the beautiful sunset silhouetting a pair of desert date trees (Balanites aegyptiaca). Each few yards seemed to bring a deeper red, and Evans obligingly stopped so we could take pictures. Finally, he told us we could stop no more, that we were late. Late for what, we asked? A surprise, he replied.

When we saw the big bonfire up in

the Aitong Hills, we knew where we were headed. We drove up and parked in the circle of

vans. Liveried waiters dispensed

sundowners from a bar set up in a clearing on the hillside and we sat back in

canvas deck chairs around  the fire and sipped our drinks looking out

over the Mara. In the dark, it was

difficult to make out the two

sharpshooters sitting on the grassy slope behind us, their rifles at the

ready. But rhinos, said someone,

absolutely hate bonfires and have

been known to charge them. Hmmm.

the fire and sipped our drinks looking out

over the Mara. In the dark, it was

difficult to make out the two

sharpshooters sitting on the grassy slope behind us, their rifles at the

ready. But rhinos, said someone,

absolutely hate bonfires and have

been known to charge them. Hmmm.

Where the sun had set a half-hour

earlier, the western sky now staged a spectacular light show. Fork lightning spawned from convection over

On Monday, March 5, we awoke

before dawn to a pleasant “Jambo, good

morning!” just outside our tent.

Doug unzipped the flap and took the tray of steaming black coffee, hot

cocoa and biscuits. “

As we drove out over the Mara,

the moon was still high in the rosy dawn sky, but the animals were already

roaming. We saw cape buffalo with the

omnipresent cattle egrets at their feet.

A spotted hyena ran skulking away through the grass and we saw

elephants, a wildebeest and her baby, and two types of gazelles: Thomson’s

gazelle (Gazella thomsonii) and Grant’s gazelle (Gazella granti). We were

forever asking our drivers which gazelle was which, but by now we knew the

difference. The Thomson’s – sometimes

called a “tommy” -- is slightly shorter (22-26 inches), lighter (35-55 lbs.)

and has a horizontal black stripe on its flank.

Most Grant’s are not striped; they’re also taller (30-36 inches),

heavier (100-145 lbs.) and have a white spot on the top of the tail. If you

want a fast photographic reference to

There were ostriches, too, and I resolved to check when I returned home the story we’d heard in another park, that an ostich’s sex is determined by which parent sits on the egg. Could such a thing actually be possible? Although I found no evidence for this in my research, what I found was that the greyish female incubates the eggs by day, and the black male incubates them by night, thus preventing detection by predators.

We saw shy, cow-like elands with their striped midsections and tried to get a good photo, but elands are forever retreating, unlike other antelopes that often seem to be posing. Such was the case with a lone topi, its blue flanks gleaming in the morning sun as it looked up at us from grazing.

Evans pointed out the various trees and shrubs of the Mara, including the savannah gardenia (Gardenia volkensii), desert date (Balanites aegyptiaca), euclea (Euclea divinorum) and orange-leafed croton bush (Croton dichogamus). This last plant, which grows in thickets in the Mara is particularly interesting. Its fragrant leaves tend to repel flies and other insects, so lions and other animals often retreat to the croton thickets in the heat of day. Along with the euclea, the Maasai also use the aromatic twigs as chewing-sticks or toothbrushes.

As we headed back to camp, we saw giraffes, a common waterbuck and her baby, and a herd of male impalas sitting in the long grasses.

Following our morning game drive,

we ate breakfast and returned to our tent

for some much-appreciated free time.

We sat on our shady veranda reading and enjoying the calls of the myriad

birds in the lodge’s trees while citrus swallowtail butterflies fluttered

lazily past. From across the river came

the incessant jangling of the cowbells on the Kalenjins’ cattle. There was something  strangely familiar to me about the bells, but

it wasn’t until I got home that I realized what it was. In the late ‘60s, a great African trumpeter

named Hugh Masekela made a hit record called Grazin’ in the Grass and the accompaniment to the brass line was --

what else? -- African cowbells! (To hear

a clip of this tune, go

to this page. Masekela also appeared

at Paul Simon’s fabulous 1987 Graceland

concert in

strangely familiar to me about the bells, but

it wasn’t until I got home that I realized what it was. In the late ‘60s, a great African trumpeter

named Hugh Masekela made a hit record called Grazin’ in the Grass and the accompaniment to the brass line was --

what else? -- African cowbells! (To hear

a clip of this tune, go

to this page. Masekela also appeared

at Paul Simon’s fabulous 1987 Graceland

concert in

Twenty feet below us in the brown

waters of the Mara River, pods of hippos (Hippopotamus

amphibius) gambolled and bellowed all day long in the shallows. Along with the white rhino, hippos are the

second largest land animals on earth after elephants, with males weighing up to

6000 pounds, females half that. Recent

DNA studies have determined that the hippo’s closest living relative is not the

pig, with whom it has always been grouped, but the whale and the porpoise. Hippos stay submerged during the day to keep

their hides from drying out and to prevent sunburn; they come out of the water

at night to graze. Adult hippos don’t

swim, but stand on the bottom and propel themselves upwards with their hind

legs. Baby hippos are born underwater

at a weight of 60 – 100 pounds and swim to the surface  for their first breath. Although their massive size would seem to

make them a danger only in water, hippos can actually run between 18 to 30

miles per hour for a distance of a few hundred yards – far and fast enough to

kill a human, which they do more than any other animal in Africa if someone

gets between them and water. Hippos

must surface every 3 – 5 minutes to breathe and do so even while asleep. The gentle sound of their breath being

exhaled as they surfaced seemed to me strangely out of scale with the animal’s

huge size, as if I were listening to someone surfacing near the dock at my

cottage. From time to time, two of the

huge hippos would open their mouths wide and clash jaw-to-jaw. I was told it was “jousting males” but often

it seemed to be a male and female showing affection or perhaps a cow and her

calf. It seemed almost surreal that

this spectacular show so close to our tent was not something that Disney had

dreamed up for Epcot, say, but a natural phenomenon that has played out in this

muddy river since time immemorial.

Amazing. (For more information on

hippos, check out this page. For excellent hippo photos, see this page.)

for their first breath. Although their massive size would seem to

make them a danger only in water, hippos can actually run between 18 to 30

miles per hour for a distance of a few hundred yards – far and fast enough to

kill a human, which they do more than any other animal in Africa if someone

gets between them and water. Hippos

must surface every 3 – 5 minutes to breathe and do so even while asleep. The gentle sound of their breath being

exhaled as they surfaced seemed to me strangely out of scale with the animal’s

huge size, as if I were listening to someone surfacing near the dock at my

cottage. From time to time, two of the

huge hippos would open their mouths wide and clash jaw-to-jaw. I was told it was “jousting males” but often

it seemed to be a male and female showing affection or perhaps a cow and her

calf. It seemed almost surreal that

this spectacular show so close to our tent was not something that Disney had

dreamed up for Epcot, say, but a natural phenomenon that has played out in this

muddy river since time immemorial.

Amazing. (For more information on

hippos, check out this page. For excellent hippo photos, see this page.)

After a swim and lunch, it was

time for our afternoon game drive. We

saw small groups of zebras grazing, a Kori bustard and lots of beautiful

giraffes. These were the common Maasai

giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalus

tippelskirchi) as opposed to the Rothschild’s giraffes we’d seen in

Our final sighting of the afternoon was an elusive warthog. But our driver Evans was disappointed. No cats! In two days, we’d not seen hide nor hair (mane?) of any lions or leopards. This was quite unusual, since the Mara is very dependable for cats and we could tell Evans was doing his best to criss-cross the savannah in hopes of finding us some. Oh well, thank goodness for Ngorongoro.

We returned to camp for sundowners, dinner and a lecture by the Mara Safari Club’s affable naturalist and butterfly specialist Mike Clifton. His talk would prepare us for next morning’s early nature walk.

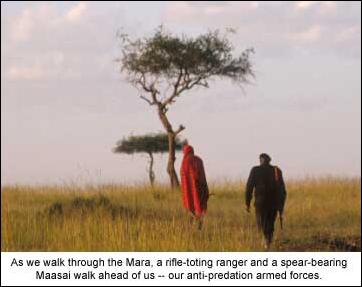

On Tuesday, March 6, once again we got our pre-dawn wake-up call complete with coffee and cocoa. Then it was off to the lodge to sign our waiver (gulp….lions, hippos, green mambas?) and head out onto the savannah for a nature walk with Mike. We felt safe when we saw that our little group was escorted by our very own two-man anti-predation squad consisting of a Maasai with his spear and a rifle-toting ranger.

Mike walked quickly over the

Mara, blitzing us with facts and figures as he pointed out trees and shrubs and

other plants. A sampling: the gardenia tree has roots that grow horizontally

in the shallow soil. There are 230

species of grasses on the Mara. Nothing

eats rat-tail grass. Red oats is

ounce-for-ounce the most nutritious grass on the savannah. The sandpaper tree is used by the Maasai to

rub down wood and because older leaves are grittier than young leaves, you can

get different sandpaper “grades” on the same tree. Waste paper flowers (Cycnium) are parasitic on the grasses in which they grow. The Maasai often burn the savannah in June or

July after the big rains to encourage grass growth. The roots of the orange-leaved croton are

completely fireproof and though flies won’t go into a croton thicket,

mosquitoes will. Nothing eats eucleas

because of the amount of phenols they contain but elephants and Maasai will

chew them, then spit them out. Termites

are “proper gardeners” because of their mushroom-growing abilities. Olive trees are native to Africa, as well as

the

As we tried to keep up, we came

upon the deep grooves made in the soil by hot-air balloons taking off from the

Mara. Mike assured us the ruts would be

gone by the next season. “

At the end of our walk, we were picked up by the vans and returned to the lodge to have breakfast. Those who skipped the walk and took a last game drive regaled us with the stories of the lions and leopards they saw. But we were happy to have had the chance to get out into the Mara and have some exercise.

Our bags were picked up and we got into the Mara Safari Clubs’ vans for the last time. Evans let me jump out at the entrance to the lodge to snap a quick shot of the beautiful blue lotus waterlilies blooming in a swamp there. I had seen these on the way in a few days back and was determined to get a photo, for this is the same native species whose petals were found sprinkled on the shroud of the 3300-year-old mummy of King Tutankhamun, when his tomb was opened by Howard Carter in 1922. A sacred flower in Egyptian mythology, extracts of blue lotus waterlilies are sold today in botanical preparations and it is also the parent of many hybrid tropical waterlilies. (For more on the blue lotus in ancient Egyptian history, see this page.)

It took us only a few minutes to reach the Mara’s little airstrip and before long, we were once again flying over the Rift Valley on our way to the final stop on our two-week safari.

Nairobi Amboseli Tarangire Ngorngoro Serengeti