March 2007 © Janet Davis

We entered  boxed lunches while sitting on a curb in the

parking lot. After all, we had a game

drive ahead of us before reaching our lodge in the middle of the park and

Micato did not want us going hungry.

boxed lunches while sitting on a curb in the

parking lot. After all, we had a game

drive ahead of us before reaching our lodge in the middle of the park and

Micato did not want us going hungry.

Serengeti comes from siringet, the Maasai word for “endless plains”, and while vast grassy plains cover about one-third of the park, the rest is woodland, riverine forest, rocky hills and rivers. The rich soil of the plains was laid down 3 to 4 million years ago, the product of volcanic ash blowing from the nearby crater highlands.

The first inhabitants of the Serengeti were ancient

hunter-gatherers. More recently, Maasai

pastoralists tended their herds there, tracking the rains and the fresh grasses

in the same way that the wildebeest and other hoofed animals do today in their  annual migration. That migration route defines the Serengeti

Ecosystem which is much larger than the official park area, more than 10,000

square miles. It includes

annual migration. That migration route defines the Serengeti

Ecosystem which is much larger than the official park area, more than 10,000

square miles. It includes

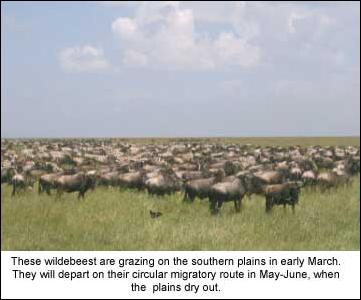

In essence, the great Serengeti

migration follows the rains. The months of February-March feature the

synchronized calving season in the southern short grass plains, when 90 percent

of the female wildebeest give birth over a 3-4 week period while grazing on the

nutritious grasses growing in the volcanic soil there. When the rains finish in May, the plains

quickly dry out and more than 1.5 million wildebeest march west and eventually

north into the Maasai Mara, moving in long, meandering columns or in herds of

thousands. The river crossings are

legendary, with masses of the animals leaping from cliffs, some to their

deaths. They arrive at the long grasses

of their  winter grazing grounds between June and July

and move slowly clockwise until November, when they circle back through the

Ngorongoro area to the southern plains.

winter grazing grounds between June and July

and move slowly clockwise until November, when they circle back through the

Ngorongoro area to the southern plains.

Along with the wildebeests, the migration includes Thomson’s gazelles, plains zebras, elands and sometimes elephants, ostriches and other wildlife. Ecologically, there is a grazing balance struck between these ungulates, with plains zebras eating the tops of the grasses, wildebeests with their blunt muzzles consuming the mid-sections, and gazelles finishing off the bases. Zebras have a better sense of sight and hearing than the wildebeest, so their cries often provide an early warning against predators.

Wildebeests (Connochaetes taurinus) are known as white-bearded gnus in

As we left the picnic area and began our drive into the park, we saw common

Maasai ostriches and a migratory European stork enjoying its winter home. And we came upon a colony of marabou storks

preening and drying their wings.

Scavengers, they are often found near garbage dumps or an animal kill

and will eat almost any animal, from grasshoppers to the hollowed-out carcass

of an elephant. In fact, their bald

heads are said to have evolved to let them dig into a freshly killed animal

without getting their feathers bloodied.

Writes Mathiessen in The

Tree Where Man Was Born: “The marabou, with its raw skull and pallid

legs, is more ill-favored still: it

takes to the air with a hollow wing thrash, like a blowing shroud, and a horrid

hollow clacking of the great bill that can punch through tough hide and lay open

carcasses that resist the hooks of the hunched vultures.” Adult marabous can reach almost five feet in

height with a wingspan of up to 10 feet.

It’s fascinating that the fine underfeathers of these large, ungainly

birds adorned stylish ladies’ hats in 19th century

Driving further into the park, we

came upon large herds of plains zebras (Equus

quagga burchelli) with their young.

Zebras are

There is little romance in zebra courtship. When a stallion wants a new filly, he must abduct her from her father’s herd. At the age of 1 – 2 years, a female zebra begins ovulating; in her monthly estrus, she adopts the time-honored adolescent stance of sticking out her tail, stretching her neck and chewing with her mouth open. (Does this sound familiar?) Stallions mill around her herd and compete for her favor by fighting with each other and her father. The stallion that finally inseminates her becomes her partner for life – along with several other kidnapped females. If she’s the first filly in a harem, she is the dominant mare with other mares and fillies subservient to her. Bachelor herds organize according to age.

If all this sounds a little

Darwinian, that’s probably because it is.

In essence, the gene pool becomes strengthened through the dominance of

a fearless alpha male. After all, if a

feckless filly went off with the  stallion with the best-looking stripes, who

knows what evolutionary mayhem might occur?

And strange as it seems, those stripes are another evolutionary

strategy. Though they appear highly

visible to us, to a color-blind lion or hyena they are very confusing, given

that zebras walk in large herds through long-bladed grasses. So, safety in numbers and in stripes.

stallion with the best-looking stripes, who

knows what evolutionary mayhem might occur?

And strange as it seems, those stripes are another evolutionary

strategy. Though they appear highly

visible to us, to a color-blind lion or hyena they are very confusing, given

that zebras walk in large herds through long-bladed grasses. So, safety in numbers and in stripes.

A zebra foal is born weighing about 70 pounds and is typically standing within fifteen minutes and nursing and running within an hour. This fast development rate is a necessity when there are predators watching the birthing and the herd must keep moving to feed on long grass. Unlike its mother, a zebra foal has a fuzzy, brown-and-white coat.

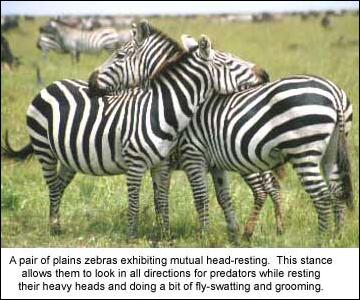

Many of the zebras had paired off and were exhibiting a trait called mutual head-resting. Largely an anti-predation stance, it allows them to rest their large heads on each other’s back, flicking flies away while gazing in opposite directions for predators. It is not part of courtship and usually involves females within a harem, siblings, or a mother and foal. (For more on the plains zebra, read this Wikipedia page.)

Soon we saw the ancient granite

outcrops jutting out of the Serengeti’s flat, grassy plains. Called inselbergs or kopjes – a Dutch/Afrikaans word  pronounced “copies” and meaning “small heads”

– they offer shade and shelter to many of the wild animals in the park. “On

the plain,” writes Mathiessen, “the

bone of Africa emerges in magnificent outcrops or kopjes, known to geologists

as inselbergs, rising like stone gardens as the land around them settles, and

topped sometimes by huge perched blocks, shaped by the wearing away of

ages. The kopjes serve as water

catchments, and in the clefts, where aeolian soil has mixed with eroded rock,

tree seeds take root that are unable to survive the alternate soaking and dessication

on the savanna, so that from afar the outcrops rise like islands on the grass

horizon.”

pronounced “copies” and meaning “small heads”

– they offer shade and shelter to many of the wild animals in the park. “On

the plain,” writes Mathiessen, “the

bone of Africa emerges in magnificent outcrops or kopjes, known to geologists

as inselbergs, rising like stone gardens as the land around them settles, and

topped sometimes by huge perched blocks, shaped by the wearing away of

ages. The kopjes serve as water

catchments, and in the clefts, where aeolian soil has mixed with eroded rock,

tree seeds take root that are unable to survive the alternate soaking and dessication

on the savanna, so that from afar the outcrops rise like islands on the grass

horizon.”

We drove around the Gol Kopjes,

hoping to see a lion or cheetah climbing down and heading out onto the plain to

get dinner. Obviously, it was a little

too early because the lions were sound asleep on the smooth rock surface and

the cheetah was snoozing in behind some shrubs and trees.

We arrived at the Serengeti Sopa

Lodge and were welcomed by the staff with damp towels for our faces and

refreshing glasses of

passion-fruit juice. Our room was lovely, the most luxurious so

far, with a king-sized bed, deep tub and stunning balcony view of the

Serengeti. (We later found out that not

all our gang enjoyed this level of accommodation which was the result of a

hotel glitch, so we endured lots of friendly griping.)

passion-fruit juice. Our room was lovely, the most luxurious so

far, with a king-sized bed, deep tub and stunning balcony view of the

Serengeti. (We later found out that not

all our gang enjoyed this level of accommodation which was the result of a

hotel glitch, so we endured lots of friendly griping.)

On Saturday, March 3rd,

we headed out for our morning game drive with Safari Director Philip along as

We passed giraffes nibbling at

acacias, a huge saddle-billed stork perched atop a tree, hippos bathing in the

We whiled away a few moments on

our morning drive by asking Philip about Tanzania’s colonial history. In his own affable way, he gave us the

25-words-or-less version of the “scramble for Africa”, the massive  19th century land grab by European

nations intent on dividing up the entire African continent amongst

themselves. In essence, said Philip,

countries like Angola and Mozambique that had been colonized by Portugal, and

Belgian colonies such as Rwanda, Burundi and Congo, fared far worse in their

post-colonial prospects than did Tanzania (Tanganyika), originally a German

colony but handed to Britain after WW I.

Once the British departed after independence,

19th century land grab by European

nations intent on dividing up the entire African continent amongst

themselves. In essence, said Philip,

countries like Angola and Mozambique that had been colonized by Portugal, and

Belgian colonies such as Rwanda, Burundi and Congo, fared far worse in their

post-colonial prospects than did Tanzania (Tanganyika), originally a German

colony but handed to Britain after WW I.

Once the British departed after independence,

As always, we were impressed with Philip’s ability to illuminate us on any topic, from the Maasai culture, to animal life, to wildflower identification, to African history. Coupled with a great sense of humor and his calm handling of all safari details (and complications), we considered ourselves lucky to have him lead our trip.

On our way to the Serengeti

Visitor Centre, Frederick pointed out the dark profile of a leopard asleep on a

branch high in an acacia. And a little further, we saw our first topi standing

on the road in front of us. At the

Centre, we toured the exhibits in the building and read about the relationship

between the Frankfurt Zoological Society and the Serengeti, including the role

of the film-making Grzimeks whose memorial we had seen at Ngorongoro. Some of the group elected to take an

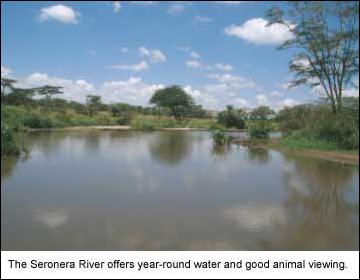

interesting nature walk around the grounds before returning past the Seronera

River to the lodge for lunch. The river

is one of several that criss-cross the

After lunch, we rested, walked

the lodge grounds (more agama lizards) and swam in the pool before heading out

on our late-afternoon game drive. As we

drove east across the plains, I was overwhelmed by the sheer size of these vast

grasslands that stretch all the way to the horizon, rippling like golden-green

waves under a massive blue sky. It’s a

landscape almost impossible  to capture on film, even in a wide-angle

shot. But I tried.

to capture on film, even in a wide-angle

shot. But I tried.

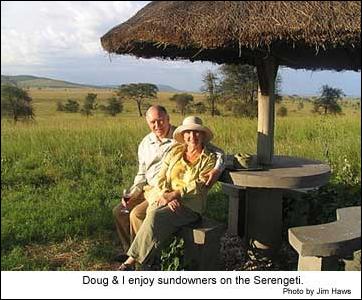

Our final surprise destination was a picnic area where sundowner cocktails were served as we enjoyed the golden light of our last afternoon in the Serengeti. After a glass of wine, it seemed like the perfect time to try out my few words of Swahili on the guides and drivers, so I worked up my courage and walked over to where they were standing. They were amused as I started singing a popular African song:

Malaika, nakupenda malaika.

Malaika, nakupenda malaika.

Ningekuoa mali we,

Ningekuoa dada,

Nashindwa na mali sina we,

Ningekuoa Malaika.

I sang two more verses, and the guys were laughing and stomping their feet by the time I’d finished. “Where did you learn that?”, one asked. I told them I’d first heard it as a teenager when I’d seen South African singer Miriam Makeba perform it in concert with Harry Belafonte. (“Malaika” means “my angel”, and the song is the lament of a young man who doesn’t have enough money to marry his girlfriend.) Having looked up the lyrics on the internet and memorized the verses phonetically, my trip gave me the chance to bring it to life. “Mama Safari”, cried the guys, jokingly alluding to Makeba’s exalted status as “Mama Africa”. (Listen to the Belafonte/Makeba duet.)

As we drove back to the lodge for dinner, we were treated to the sight of a full moon rising over the Serengeti.

Early Sunday morning, we checked

out and headed to the nearby Seronera Air Strip for the three short-hop flights

to Arusha,

Lengai is a stratovolcano, a

steep, conical type of volcano with viscous magma that flows easily, unlike

flatter shield volcanoes such as