March 2007 © Janet Davis

Mount

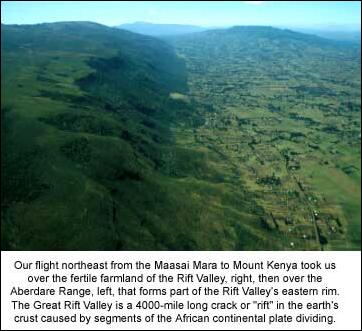

Once again, our group was divided into three small planes

chartered by Micato to take us northeast from the Mara’s airstrip over the

I had come to enjoy our scenic flights over the Eastern Rift

Valley with its fertile farmland, volcanic craters and ridged escarpments. In fact, I sometimes wished I could ask  the pilot to veer a little closer to a

volcano or fly along a valley wall. It

was fascinating to get a bird’s eye view of one of earth’s finest examples of plate

tectonics, or continent-building.

I came home wanting to know a little more about the geological

beginnings of this place we’d been. So

-- in an oversimplified African nutshell -- this is roughly how it goes. (If you’re not interested, please skip the

next six paragraphs).

the pilot to veer a little closer to a

volcano or fly along a valley wall. It

was fascinating to get a bird’s eye view of one of earth’s finest examples of plate

tectonics, or continent-building.

I came home wanting to know a little more about the geological

beginnings of this place we’d been. So

-- in an oversimplified African nutshell -- this is roughly how it goes. (If you’re not interested, please skip the

next six paragraphs).

Once upon a time, about 150 million years ago, Africa was

not a separate continent but part of a supercontinent geologists call Gondwana which also encompassed what are

now the land-masses of South America, Antarctica,

Of course, land-masses do not just “drift” or “rift”

magically away from each other. Their

movements come as a result of boundary interactions between the the planet’s tectonic plates. These plates make up earth’s lithosphere and are composed of the

outer oceanic or continental crust

and the uppermost part of the mantle. The lithosphere ranges in thickness from a

few miles to more than 200 miles under stable continental shields. It floats on the weak, warm mantle region

below, the asthenosphere, where

temperatures can melt rock and magma can be released upwards from deeper in the

earth. According to  very,

very slow-moving liquid, whereas the lithosphere is a buoyant solid. So the plates are like icebergs floating in

an ocean, i.e. the asthenosphere.” (For

more on the earth’s lithosphere and asthenosphere, see

this page.)

very,

very slow-moving liquid, whereas the lithosphere is a buoyant solid. So the plates are like icebergs floating in

an ocean, i.e. the asthenosphere.” (For

more on the earth’s lithosphere and asthenosphere, see

this page.)

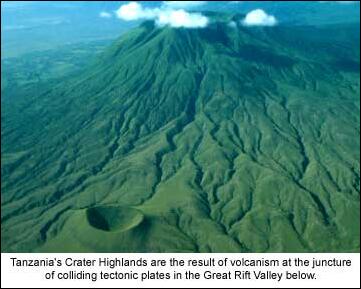

When plate boundaries meet, violent events sometimes occur,

including earthquakes, volcanoes and tsunamis. An example is the

2004 Asian tsunami caused by buckling at a subduction

zone on the ocean floor during a powerful earthquake 19 miles below sea

level. The earthquake occurred when the

edge of an oceanic plate slipped suddenly below a continental plate. (For more

on tsunamis and earthquakes, see this page

from PBS.) The Rift Valley’s Crater

Highlands in

Once the African

continental plate finally stood alone, large parts of it anchored with

stable Precambrian bedrock (like those granite outcrops or kopjes in the Serengeti), it became subject to its own tectonic

forces, splitting or “rifting” along the unstable African Rift Zone

into two sections, the Nubian subplate in the west, and the Somalian subplate

in the east. The crack between the two

eventually widened into the 4000-mile-long Rift Valley, which begins in Turkey

and extends south and east through Ethiopia, Kenya and Tanzania to

Mozambique. The East African Rift

System consists of western and eastern segments. The western is called The Albertine Rift and

goes through  Somalia, Ethiopia, Eritrea and Dijbouti, from

the “old” African continent. Needless

to say, this is exciting researchers who believe they are

witnessing the birth of a new ocean.

Somalia, Ethiopia, Eritrea and Dijbouti, from

the “old” African continent. Needless

to say, this is exciting researchers who believe they are

witnessing the birth of a new ocean.

Technically, the Rift Valley is a graben, defined by the U.S. Geological Survey as “a

down-dropped block of the earth’s crust resulting from extension or pulling of

the earth’s crust”. But looks are

misleading; even though this “valley” appears low and verdant beneath its high

walls, much of

Therefore, Professor Culshaw concludes, plate tectonics are

really responsible for the supremacy of

On to the

After landing at the airstrip in the little town of

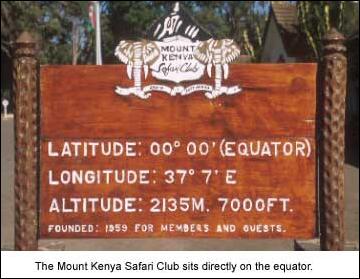

On arriving at the Mount Kenya Safari Club, we were served refreshing drinks and picked up our room keys. If Micato thought we’d appreciate a luxurious finale at the end of our whirlwind safari through five game parks in two countries, they were absolutely right. Our suite in a cottage near the bottom of the club’s grounds was lovely. But I was keen to learn more about the various trees and plants on the property, so I booked a late afternoon walking tour with Simon Mureitha, one of the club’s naturalists. In the meantime, we ate lunch in the club’s light-filled dining room.

Mount Kenya Safari Club has a storied

history. Currently owned by Fairmont

Hotels, it was founded in 1959 by actor William Holden and two partners who bought

2000 acres around the old British hotel, the Mawingo (est. 1939), re-opening it

as a private club and wildlife sanctuary.

Founding members included Conrad Hilton, Bob Hope, Clark Gable, John

Wayne, Walt Disney, Joan Crawford, Lord Mountbatten and Sir Winston Churchill. More recent members include the Aga Khan,

the presidents of

Mount Kenya Safari Club has a storied

history. Currently owned by Fairmont

Hotels, it was founded in 1959 by actor William Holden and two partners who bought

2000 acres around the old British hotel, the Mawingo (est. 1939), re-opening it

as a private club and wildlife sanctuary.

Founding members included Conrad Hilton, Bob Hope, Clark Gable, John

Wayne, Walt Disney, Joan Crawford, Lord Mountbatten and Sir Winston Churchill. More recent members include the Aga Khan,

the presidents of

My nature walk with Simon around the club’s current 100-acre

property took us down into the area around the

Sunbirds flitted around the club’s cannas and aloes,

demonstrating an interesting botanical fact:

most tropical plants with long, funnel-shaped orange and red blooms have

evolved to be pollinated by birds, rather than bees or butterflies. Bird vision tends to be  most acute in the orange-red light spectra,

allowing them to find such flowers easily.

In fact, while I was at the pool the next day, I stood quietly in the

hot sun trying to photograph a sunbird flitting about in a tall aloe

plant. (And it occurred to me for about

the fiftieth time during this trip that it would have been great to have a

longer lens than my 75-300 telephoto for all those tiny birds high above me.)

most acute in the orange-red light spectra,

allowing them to find such flowers easily.

In fact, while I was at the pool the next day, I stood quietly in the

hot sun trying to photograph a sunbird flitting about in a tall aloe

plant. (And it occurred to me for about

the fiftieth time during this trip that it would have been great to have a

longer lens than my 75-300 telephoto for all those tiny birds high above me.)

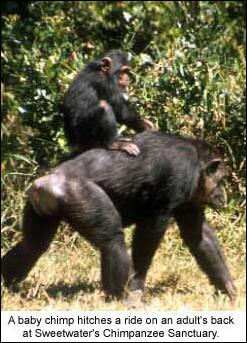

Wednesday, March 7th would be our last day on safari and we had two stops on our morning game drive, the Sweetwaters Chimpanzee Sanctuary and The Rhino Sanctuary. Both are contained in the Ol Pejeta Conservancy, a 90,000 acre wildlife reserve which was extended in 2004 to include the 24,000 acre Sweetwaters Animal Reserve and the luxurious Sweetwaters Tented Camp. Sweetwaters was once called Ol Pejeta Ranch; it was founded by Lord Delamere of Colonial fame and went through various owners including the infamous Saudi industrialist, playboy and arms dealer Adnan Khashoggi. The Ol Pejeta Conservancy is now owned by the conservation body, Fauna & Flora International.

The Sweetwaters Chimpanzee Sanctuary was established in 1993

by renowned primatologist Jane Goodall, along

with Lonrho Africa and the Kenya Wildlife Service. It started with three orphaned chimpanzees

who were relocated from the Jane Goodall

Institute (JGI) in  interest in the higher primates. She was hired in

interest in the higher primates. She was hired in

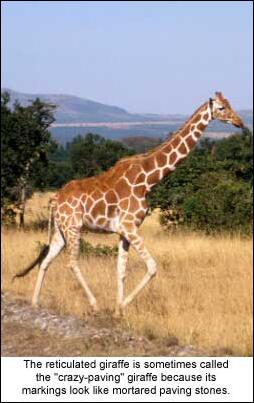

Upon entering Ol Pejeta Conservancy, we completed our giraffe-spotting hat-trick when a third sub-species of the common giraffe – the beautiful reticulated giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis reticulata) – crossed the road in front of our van. The reticulated giraffe is also nicknamed the “crazy-paving” giraffe because its reddish coat resembles paving stones separated by white mortar.

Our group gathered in an elevated structure where we could

look down into the sanctuary over a tall electrified fence built to keep

elephants out of the chimpanzee habitat.

We listened to guide Charles Musasia as he told us about the 41

chimpanzees now cared for on the JGI’s 247 acres at Sweetwaters, including

three that were born there. Generally,

he said, breeding is not allowed and female chimps are given the Norplant

contraceptive vaccine. But ‘accidents’

have happened, including one sweet baby chimp we saw  riding on the back of an adult across the

river, when we took a walk through the sanctuary later. The river serves to separate two populations

of chimpanzees within the reserve. The

aim of the JGI is to rehabituate chimpanzees to life in the wild; to that end,

the sanctuary is only open 1-1/2 hours in the morning and 1-1/2 hours in the

afternoon so the chimps don’t become too accustomed to people. The life expectancy of chimpanzees in the

wild is 30-35 years; in a protected environment they can live 50-60 years. In my later reading, I found that according

to research being

done at

riding on the back of an adult across the

river, when we took a walk through the sanctuary later. The river serves to separate two populations

of chimpanzees within the reserve. The

aim of the JGI is to rehabituate chimpanzees to life in the wild; to that end,

the sanctuary is only open 1-1/2 hours in the morning and 1-1/2 hours in the

afternoon so the chimps don’t become too accustomed to people. The life expectancy of chimpanzees in the

wild is 30-35 years; in a protected environment they can live 50-60 years. In my later reading, I found that according

to research being

done at

As the day grew hot, we headed to The Rhino

Sanctuary nearby. Here, we met

a black rhinoceros named Morani (Maasai for

warrior) whose life story was rather poignant.

He was born in 1974 at

The population of black rhinoceroses (Diceris bicornis) in  conservation issues and anti-poaching

legislation. We finished our stay at

the Rhino Sanctuary with a short visit to the excellent little museum at the

entrance to Morani’s reserve.

conservation issues and anti-poaching

legislation. We finished our stay at

the Rhino Sanctuary with a short visit to the excellent little museum at the

entrance to Morani’s reserve.

As we drove out of Ol Pejeta, we passed a group of oryxes standing at a salt lick. Driving back towards the hotel, we saw small school children heading home for lunch and asked Nathan to stop the van so we could hand out pens and pencils. They eagerly held up their hands to grab the goodies with big, happy smiles on their little faces.

After lunch, some of the group elected to play golf on the

9-hole course, others to visit the animal sanctuary Holden established on the

hotel grounds. I changed into my bathing

suit, grabbed my book and headed to the pool where I ordered a gin-and-tonic

and retreated to a chaise lounge.

Although the sun was hot, the water in the pool was freezing but taking

a swim and lounging in the sun made me feel that I’d at least had a few hours

of traditional holiday down-time.

However, anyone who’s been on safari will tell you that you don’t go to

Our last night held some nice surprises. After cocktails, group photos and speeches on the club’s terrace, we all loaded into our vans and headed down by the Likii river. Here, we found a buffet table, barbecues, dining tables and a bar – all set up in a dirt-floored clearing. We clinked our glasses to toast a fabulous safari, new friends and fantastic memories that would stay with us forever, then we filled up our plates at the buffet. My own little surprise was a CD I’d brought along containing “golden-oldies” from the 50s and 60s -- our vintage -- and when the background music stopped and Bobby Darin came on singing ‘Dream Lover’, the party got going in earnest. We laughed and sang and kicked up our heels on the dirt dance floor under the stars until Philip announced it was time to call it a night.

On Thursday, March 8th, we checked out, drove back to the

airport at Nanyuki, hugged Nathan goodbye one more time, and flew back to

So, farewell for now,

Nairobi Amboseli Tarangire Ngorngoro Serengeti Maasai Mara

View Janet’s Africa Photo Gallery

E-Mail

Janet with Comments or Questions