March 2007 © Janet Davis

To celebrate our 30th

anniversary, my husband Doug & I joined  34 other travellers on a 2-week safari to

34 other travellers on a 2-week safari to

It was presented by Micato

Safaris of

The Essence of Safari

The word safari is Swahili for

“journey” and this journey was unlike any other we’ve taken. It introduced us to a landscape both

mythical and magical, an enduring and vast palette on which nature paints in

myriad brushstrokes and hues. There are  the bold, jutting, vertical lines of the

cliffs, volcanoes and intricately folded ridges of the Rift Valley, as glimpsed

from the window of our small plane. The

pale horizontal washes of green, taupe and gold that color the endless grassy

plains of the Serengeti. The squiggly

brushstrokes of the muddy red rivers like the Seronera and Mara. The sparkling

whites outlining the soda lake shores.

The dark-green swirls of the red thorn acacias carpeting Ngorongoro’s

slope and the Mondrian-like blocks of savannah, bush, hills and sky in the

Maasai Mara.

the bold, jutting, vertical lines of the

cliffs, volcanoes and intricately folded ridges of the Rift Valley, as glimpsed

from the window of our small plane. The

pale horizontal washes of green, taupe and gold that color the endless grassy

plains of the Serengeti. The squiggly

brushstrokes of the muddy red rivers like the Seronera and Mara. The sparkling

whites outlining the soda lake shores.

The dark-green swirls of the red thorn acacias carpeting Ngorongoro’s

slope and the Mondrian-like blocks of savannah, bush, hills and sky in the

Maasai Mara.

And animals -- everywhere

animals! Birds in fantastical hues. The

heralded big five of the old game hunters, beginning with the towering

elephants trooping in absolute silence between our safari vans to reach

Amboseli’s abundant swamps so they could splash in the water and wallow in the

mud.  Antelopes of all leaps and sizes. Graceful giraffes with their long, steady

gazes. Legions of wandering wildebeests

and zebra herds in all their striped splendor.

And hippos surfacing in the murky

Antelopes of all leaps and sizes. Graceful giraffes with their long, steady

gazes. Legions of wandering wildebeests

and zebra herds in all their striped splendor.

And hippos surfacing in the murky

We learned a little – not nearly

enough – about the people of

What follows on these seven web pages is a journal of our 13 days on safari. I have written it in some detail so I’ll be able to recall all the amazing elements years later. I’ve also tried to expand my knowledge of what I saw in Africa, by learning when I got home what I might have discovered there, but simply didn’t have the time to absorb.

Those who wish to skip the prose will hopefully still enjoy the photos. And for larger versions of these photographs, as well as a few additional images, I invite you to have a look at my Africa photo gallery.

After a 7-hour flight from  flight from

flight from

Bright and early some 6 hours later, we met the other 34 trip members for breakfast, followed by a general briefing by Philip Rono, our genial Safari Director, and a lilting talk by Rakita, a Maasai elder who acts as an “ambassador” on the lifestyle of his people. Then, wearing our new Micato safari hats, we boarded the buses for our Nairobi-area tour.

Our first stop was the Giraffe Centre in

Langata, just outside

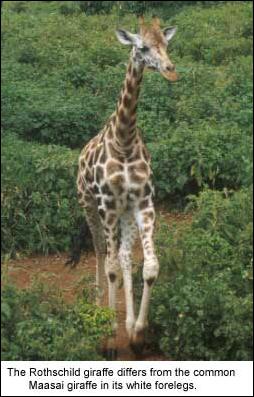

With their dictinctive lower-leg

“white socks” leading the way, the giraffes approached the Centre’s feeding

platform where they exchanged giraffe kisses (the 18-inch prehensile or

clasping tongue is said to impart antiseptic properties) for pelleted

food. We learned that a giraffe’s blood

pressure is more than twice that of humans to pump blood up that 6-foot neck;

that their normal gestation period is 15 months but can be prolonged three

months to ensure favorable conditions; they can run up to 55 kilometers per

hour; and that they normally live 20-30 years.

With a  population of 426 Rothschild’s giraffes now

in the wild (including many bred at the Centre) and a generation of Kenyan

schoolchildren educated as to their needs, the Giraffe Centre is a good example

of the recent focus in East Africa on the priceless heritage of wild animals,

often held in contempt by earlier generations of Africans, especially nomadic

herders, who saw them as a threat to their livestock.

population of 426 Rothschild’s giraffes now

in the wild (including many bred at the Centre) and a generation of Kenyan

schoolchildren educated as to their needs, the Giraffe Centre is a good example

of the recent focus in East Africa on the priceless heritage of wild animals,

often held in contempt by earlier generations of Africans, especially nomadic

herders, who saw them as a threat to their livestock.

Back on the bus, we were off to the Karen Blixen Museum. Built in 1912, the house and its surrounding

gardens were home to Blixen from 1917 to 1931, centered on what was then a

6,000-acre coffee plantation. These were

the Colonial years when the Ngong Hills were known as the White Highlands,

describing the European settlers like Karen and her husband, Count Bror Von

Blixen, who emigrated to

Countess Von Blixen would not, of

course, have ensured her place in Danish and African history were it not for Out

of Africa, the book she wrote on her return to Denmark after drought

and the Depression forced her to give up the farm. Under the pen name Isak Dinesen (it was

unacceptable for women to write such books), she began her memoir with the

immortal line: “I had a farm in

For me, the book was infinitely more interesting than the movie, with Blixen carefully describing her relationships with her African farm workers, members of adjacent tribes and other colonials. Having just read it, I was eager to walk through the rooms she described, to see the cuckoo clock that so delighted the young Kikuyu goat-herders who crowded into the house to hear it chirp out the hour. “As the cuckoo rushed out at them, a great movement of ecstasy and supressed laughter ran through the group. It also sometimes happened that a very small herdboy, who did not feel any responsibility about the goats, would come back in the early morning all by himself, stand for a long time in front of the clock, now shut up and silent, and address it in Kikuyu in a slow sing-song declaration of love, then gravely walk out again.”

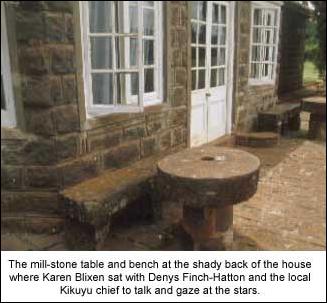

I also paused at the mill-stone table behind the house where Blixen had sat with Chief Kinanjui, head of the local Kikuyus, as they finalized the penalty for a shooting accident on her farm and where she watched the stars with Finch-Hatton (her lover, though the language in the book was necessarily ambiguous). “From the stone seat behind the mill-stone, I and Denys Finch-Hatton had one New Year seen the new moon and the planets of Venus and Jupiter all close together, in a group on the sky….”.

As we left the museum and drove

down  Karen Shopping Centre, Karen-this and

Karen-that, I recalled a passage at the end of the book as Blixen prepares to

leave

Karen Shopping Centre, Karen-this and

Karen-that, I recalled a passage at the end of the book as Blixen prepares to

leave

It seemed paradoxical, yet fitting, that the sad, lonely woman who had written so movingly of her last days in Africa should now be remembered in the streets, buildings and parks of the Ngong Hills she had once so adored. (For more on Karen Blixen, visit the Danish site devoted to her life, family and work.)

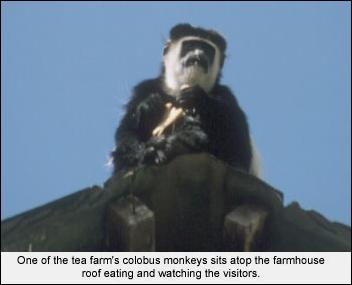

Soon, the bus was wending its way

even higher into the lush, green Limuru Highlands as we approached our final

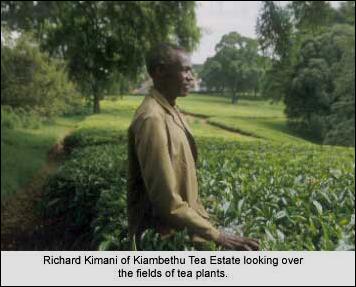

Lunch at tables on the lawn was

followed by a tea lecture from Fiona, who demonstrated how it is only the top

two succulent leaves and  uppermost bud of the tea plant (Camellia sinensis) which are

harvested. As she spoke, I sneaked away

to the gate at the bottom of the garden, where Fiona’s resident forest reserve

expert, Richard Kimani, showed me the fields of tea plants and posed for my

camera.

uppermost bud of the tea plant (Camellia sinensis) which are

harvested. As she spoke, I sneaked away

to the gate at the bottom of the garden, where Fiona’s resident forest reserve

expert, Richard Kimani, showed me the fields of tea plants and posed for my

camera.

Soon, we boarded the bus back to the Norfolk Hotel. After a brief rest and shower, it was back on the bus -- this time to cocktails and dinners at Lavington, the home of Micato’s gracious owners, Jane and Felix Pinto. With a twinkle in her eye, Jane told us how Micato got its name many years ago, explaining how she abbreviated the name of their original company, Mini-Cabs & Tours, to the first two letters of each word. A sumptuous buffet was followed by a birthday cake and “Hakuna Matata” greetings sung and danced by the Lavington household staff for all whose birthdays would fall during the 2-week safari.

As the evening and our first day

in

Next: Amboseli National

Park, Kenya