March 2007 © Janet Davis

Ngorngoro Crater

&

It was late afternoon as we

ascended the Mbulu Plateau and then drove up the steep and twisty road into

Ngorongoro’s eastern highland forest.

One blind curve saw  us suddenly face-to-face with a large

passenger bus barrelling down the hillside in the middle of the road.

us suddenly face-to-face with a large

passenger bus barrelling down the hillside in the middle of the road.

On the crater rim, we passed a

monument to the German zoologist Bernhard Grzimek

and his son Michael

Grzimek who were among the first to help protect wildlife habitat in

The sky was darkening as we reached the

Crater Lookout giving us our first glimpse over Ngorongoro, a UNESCO World

Heritage Site since 1979. Careful not to

let our legs touch the stinging nettles at the edge, we stood on our toes to

get the best shot of the massive crater, technically called a caldera. A caldera – “boiling pot” or “caldron”

-- is what’s left of a massive volcano

that erupts explosively in all directions, blowing out all its magma before

collapsing inwards on itself. Some,

like

The sky was darkening as we reached the

Crater Lookout giving us our first glimpse over Ngorongoro, a UNESCO World

Heritage Site since 1979. Careful not to

let our legs touch the stinging nettles at the edge, we stood on our toes to

get the best shot of the massive crater, technically called a caldera. A caldera – “boiling pot” or “caldron”

-- is what’s left of a massive volcano

that erupts explosively in all directions, blowing out all its magma before

collapsing inwards on itself. Some,

like

Before Ngorongoro exploded and

collapsed 2 to 3 million years ago, its cone is thought to have been more than

14,100 feet (4587 meters) in height.

With its floor measuring 11-12 miles from east to west and 8-9 miles

north to south, Ngorongoro’s 102 square miles is small compared to other

calderas in Chile, New Zealand, Indonesia and the 1200 sq. mi. caldera

underlying Yellowstone Lake, which formed 600,000 years ago during an explosive

eruption with a magma flow 1000 times as large as that of Mt. St. Helen’s. (For  an interesting look at calderas, visit this page.)

an interesting look at calderas, visit this page.)

Although close to the equator,

Ngorongoro’s elevation keeps it cool year-round with the highest point on its

eastern rim measuring 7,400 feet (2388 meters) above sea level and the lowest

at

We arrived at Ngorongoro Sopa Lodge in near-darkness, all of us anxious to get out, stretch our legs and have a stiff drink. After checking into our room, where two rocking chairs sat invitingly in front of a full-length window overlooking the crater slope, we headed back to the main lodge for cocktails, a trip briefing by Philip and dinner. Then it was off to bed.

In the morning, we drove into the

crater through a shade-dappled forest of red thorn acacias (Acacia lahigh) hung with Spanish  moss and lichens. As the road flattened out, the trees grew

more sparse and soon we were driving through grassy plains. We saw herds of zebras marching in their

typical single-file “anti-predation procession” while others grazed quietly by

the side of the road, their pretty striped tails swishing from side to side

across their striped rumps. A day-old

wildebeest – also called a white-bearded gnu -- tested out its legs by running

alongside its mother. With rain

year-round in the crater, birthing of both wildebeest and zebras continues

throughout the year and it is always fraught with danger: Wrote Mathiessen: “Wildebest

calves can usually run within ten minutes of their birth, but even this may be

too slow; I have seen a lioness, still matted red from a feed elsewhere and too

full to eat, walk up and swat a newborn to the ground without bothering to

charge, and lie down on it without biting.”

moss and lichens. As the road flattened out, the trees grew

more sparse and soon we were driving through grassy plains. We saw herds of zebras marching in their

typical single-file “anti-predation procession” while others grazed quietly by

the side of the road, their pretty striped tails swishing from side to side

across their striped rumps. A day-old

wildebeest – also called a white-bearded gnu -- tested out its legs by running

alongside its mother. With rain

year-round in the crater, birthing of both wildebeest and zebras continues

throughout the year and it is always fraught with danger: Wrote Mathiessen: “Wildebest

calves can usually run within ten minutes of their birth, but even this may be

too slow; I have seen a lioness, still matted red from a feed elsewhere and too

full to eat, walk up and swat a newborn to the ground without bothering to

charge, and lie down on it without biting.”

A massive cape buffalo relaxed in a large mud

puddle while others stood nearby grazing, and a few Grant’s gazelles watched us

drive by. We ticked Kori bustard and

Abdim’s stork off our Ngorongoro bird list and noted the flocks of lesser

flamingoes in

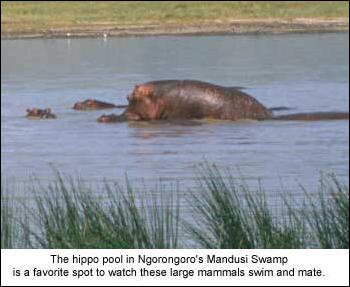

Hippos were busy mating in the Mandusi swamp,

some of an estimated 120 of the large mammals in the crater. In winter, they might remain on land part of

the the day, but during

Hippos were busy mating in the Mandusi swamp,

some of an estimated 120 of the large mammals in the crater. In winter, they might remain on land part of

the the day, but during

And through our binoculars, we saw black rhinos in the distance. Their numbers – estimated at about 20 in the crater -- are increasing because of the Black Rhino Preservation Program, a joint program between the Frankfurt Zoological Society and the Ngorongoro Conservation Area Authority that commenced in 1993.

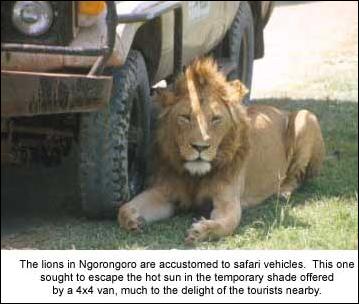

Since it was the first day of the month, we thought it highly appropriate that March should “come in like a lion”, for Ngorongoro gave us our first look at two majestic male lions (Panthera leo). Did I say majestic? Well, they would have been if they hadn’t seemed quite so bored. One ambled over from his spot in the grass to plunk down languidly in the cool shade of a safari van tire, pointedly ignoring the clicking of the cameras a few feet above his short mane, which was covered in burrs. The other gazed around briefly before tucking in to slumber peacefully amidst grasses studded with white-ink-flowers (Cycnium tubulosum) -- also called waste-paper flowers because they resemble discarded tissues. He looked for all the world like a Disney extra, rather than the terrifying beast he’s meant to be.

In an article

at nationalgeographic.com, writer Philip Caputo called lion-watching “hours and hours of boredom punctuated by

moments of sheer boredom, waiting for the lazy beasts to do something.” These two seemed to be good examples of that

sluggish work ethic -- though to be

fair, lions are mostly nocturnal hunters.

In an article

at nationalgeographic.com, writer Philip Caputo called lion-watching “hours and hours of boredom punctuated by

moments of sheer boredom, waiting for the lazy beasts to do something.” These two seemed to be good examples of that

sluggish work ethic -- though to be

fair, lions are mostly nocturnal hunters.

Continuing across the crater floor on our way to our lunch at the Ngoiyokitok picnic site, we saw a few female lions hiding in the grasses. Hopefully, they’d still be around on our way back.

At the picnic area, the Micato drivers and guides circled the vans and laid out a delicious buffet lunch with wine. Because I was so intent on photographing the giant papyrus reeds at the water’s edge and eavesdropping on British bird-watchers pointing out yellow wagtails and other feathered friends, I missed Philip’s warning about eating lunch inside the vans to thwart the black kites that swoop down to grab bits of food. Consequently, I felt the wings beat just over my head -- but managed to hold onto my piece of chicken.

After lunch, some of us elected to return to the lodge a little early, skipping the afternoon game drive. On the road away from the picnic area, we saw Thomson’s gazelles and two pairs of Maasai ostriches. But we hadn’t gone far when the radios crackled: “Simba!” We saw a few safari vans parked where we’d spotted the female lions earlier. With a long procession of zebras now passing right in front of the cats, which numbered at least five, there was great anticipation that we might actually see a kill! One lioness was clearly leader of the pack, creeping slowly forward, her head rising periodically as she assessed her chances; the others hid in the grasses to one side. Suddenly, a single zebra approached, completely isolated from those in front and behind. Oh oh! Would this be it?

Um, nope. What we discovered is that lions are verr..rr..rrr..y slow stalkers. The solitary zebra passed safely by and its

herd soon closed ranks. “Nothing is

happening here,” said

The non-stalking reminded me of a

passage in Peter Mathiessen’s book The

Tree Where Man Was Born about a zebra mare with a “slash of claws across the stripings of her quarters”, clearly the

result of a failed lion attack: “It seemed strange that an attacking lion

close enough to maul could have botched the job, but the zebra pattern makes it

difficult to see at night, when it is most vulnerable to attack by lions, and

zebra are strong animals; a thin lioness that I saw once at Ngorongoro had a

broken incisor hanging from her jaw that must have been  the

work of a flying hoof.” Mathiessen

went on to say that lions are such inefficient hunters that starvation is their

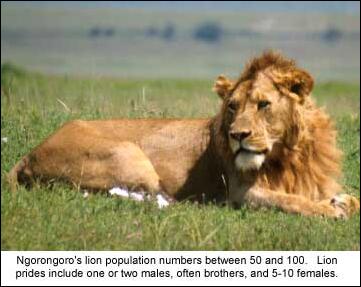

greatest threat. Though Ngorogoro’s

population might not be the best hunters in the animal kingdom, the year-round

availability of prey there ensures that they do not go hungry.

the

work of a flying hoof.” Mathiessen

went on to say that lions are such inefficient hunters that starvation is their

greatest threat. Though Ngorogoro’s

population might not be the best hunters in the animal kingdom, the year-round

availability of prey there ensures that they do not go hungry.

We were at the base of the crater slope heading up to the lodge when Doug said: “Wait! There’s an animal with spotted fur on the side of the road! I think it’s a leopard!” By the time the van stopped, whatever it was had moved into the long grasses. Then another pair of ears were spotted. Mother and cub?

“Where did it go?” we asked each

other.

Back at the lodge, still euphoric from the leopard sighting, Doug & I settled into our rocking chairs overlooking the crater, where we took a rare break to actually read the books we’d brought along and have a rest before cocktails and dinner.

On Friday March 2nd,

we breakfasted and departed Ngorongoro early in the morning, the six vans

tracing the crater’s eastern rim before heading northwest for the 87-mile

journey to the Seronera area of

oldupaii. What he heard was “olduvai”, and the rest is

history. But It was fossils found in

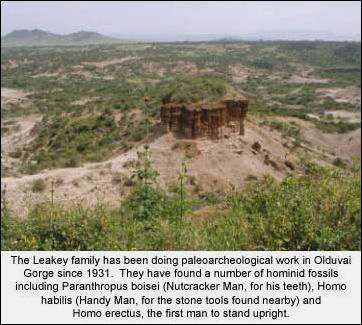

1913 by German geologist Hans Reck that inspired Kenyan-born Louis Leakey to

begin serious archaeological work in the gorge.

oldupaii. What he heard was “olduvai”, and the rest is

history. But It was fossils found in

1913 by German geologist Hans Reck that inspired Kenyan-born Louis Leakey to

begin serious archaeological work in the gorge.

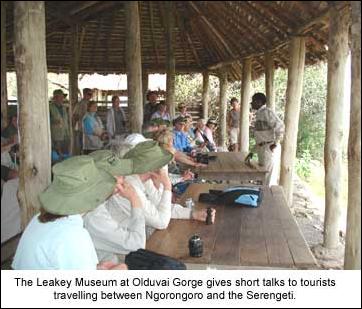

As we sat in a little open-walled building listening to a talk from a museum staff member, we gazed out at the prominent tower of land before us. The reddish upper layer, the Naisiusiu Beds, have been carbon-dated at 10,500 – 17,550 years and contain Middle Stone Age artifacts. In composition, this windborne volcanic soil is similar to the Serengeti plains nearby. The very bottom of the gorge is composed of black basalt, deposited some 2 million years ago when boiling lava flowed from the Olmoti Volcano nearby into what was then a shallow alkaline lake. Between the top of the tower and the gorge’s bottom layer are five stratigraphic beds representing more than 200 feet of spectacular archaeological and fossil history.

Discoveries made at Olduvai include OH5, Paranthropus boisei (Australopithecus boisei) or “Nutcracker Man”, a 1.8 million-year-old hominid ancestor with gorilla-sized teeth found in 1959 by Mary Leakey in the lowest strata, Bed I. Also found in Bed I were 1.9 million-year-old-tools. In 1960, their son Jonathan Leakey found the 1.75 million-year-old skull of OH7, Homo habilis, the first-known hominid. He was nicknamed “Handy Man” because he is presumed to have used the primitive tools found in the same bed.

Fossils of gigantic giraffes, buffaloes,

rhinos and elephants were also found in Beds I and II, their size a consequence

of the moist, favorable conditions in the area some 1.5 million years ago. The upper part of Bed II revealed 1.2

million-year-old fossils of Homo erectus

olduvaiensis, man now having learned to stand upright and hunt those large

beasts. As Peter Mathiessen notes: “Tool-users

such as Homo erectus and his contemporaries, who were large creatures

themselves, hunted mastodonts, gorilla-sized baboons, wild saber-tusked pigs

the size of hippopotami, and wild sheep as large as buffalo….”. (Just 10 days after my visit to Olduvai, I

was able to connect the dots as I stood before a glass display case in

Fossils of gigantic giraffes, buffaloes,

rhinos and elephants were also found in Beds I and II, their size a consequence

of the moist, favorable conditions in the area some 1.5 million years ago. The upper part of Bed II revealed 1.2

million-year-old fossils of Homo erectus

olduvaiensis, man now having learned to stand upright and hunt those large

beasts. As Peter Mathiessen notes: “Tool-users

such as Homo erectus and his contemporaries, who were large creatures

themselves, hunted mastodonts, gorilla-sized baboons, wild saber-tusked pigs

the size of hippopotami, and wild sheep as large as buffalo….”. (Just 10 days after my visit to Olduvai, I

was able to connect the dots as I stood before a glass display case in

In Bed III, the soil is characterized by its reddish-brown color; this bed dates from when the salt lakes formed. Bed IV (c. 800,000 years ago) contains sophisticated stone tools and more H. erectus fossils. The Masek Beds (600,000 – 400,000 years ago) were formed by Kerimasi, another nearby volcano, now extinct. The Ndutu Beds, next to the uppermost layer, are between 100,000 to 30,000 years old and contain Middle Stone Age artifacts.

For its profound importance to

mankind, Olduvai is a rustic place -- wind-swept and sun-baked with humble

buildings that make little footprint on the landscape. But the stunning discoveries unearthed there

have altered forever our understanding of our own place on this planet. (For more on the Leakey family, see their website. For more on the topography and discoveries at

Back in the vans, some of us laden with lovely little souvenirs from Olduvai’s gift shop, we continued west towards Serengeti’s eastern Naabi Gate. As we drove through the adjacent plain dotted with thousands of grazing wildebeests and zebras, we gained our first clues about the size of the famous migration.

Nairobi Amboseli Tarangire Maasai Mara Mount Kenya